My Favourite Cricketer sees the teams at Balanced Sports and World Cricket Watch invite the best cricket writers and bloggers to tell us who their favourite cricketers are - and, more importantly, tell us why they stand out. Today's submission is by S.A. Rennie of Legside Filth. You can find Legside Filth on the web at www.legsidefilth.com, or on Twitter at @legsidefilth

I

never saw my favourite cricketer play; he died 56 years before I was

born. But like a cricketing Alexander the Great he left behind him a

legacy of achievement, literature, and myth, and changed the face

of batting forever.

It

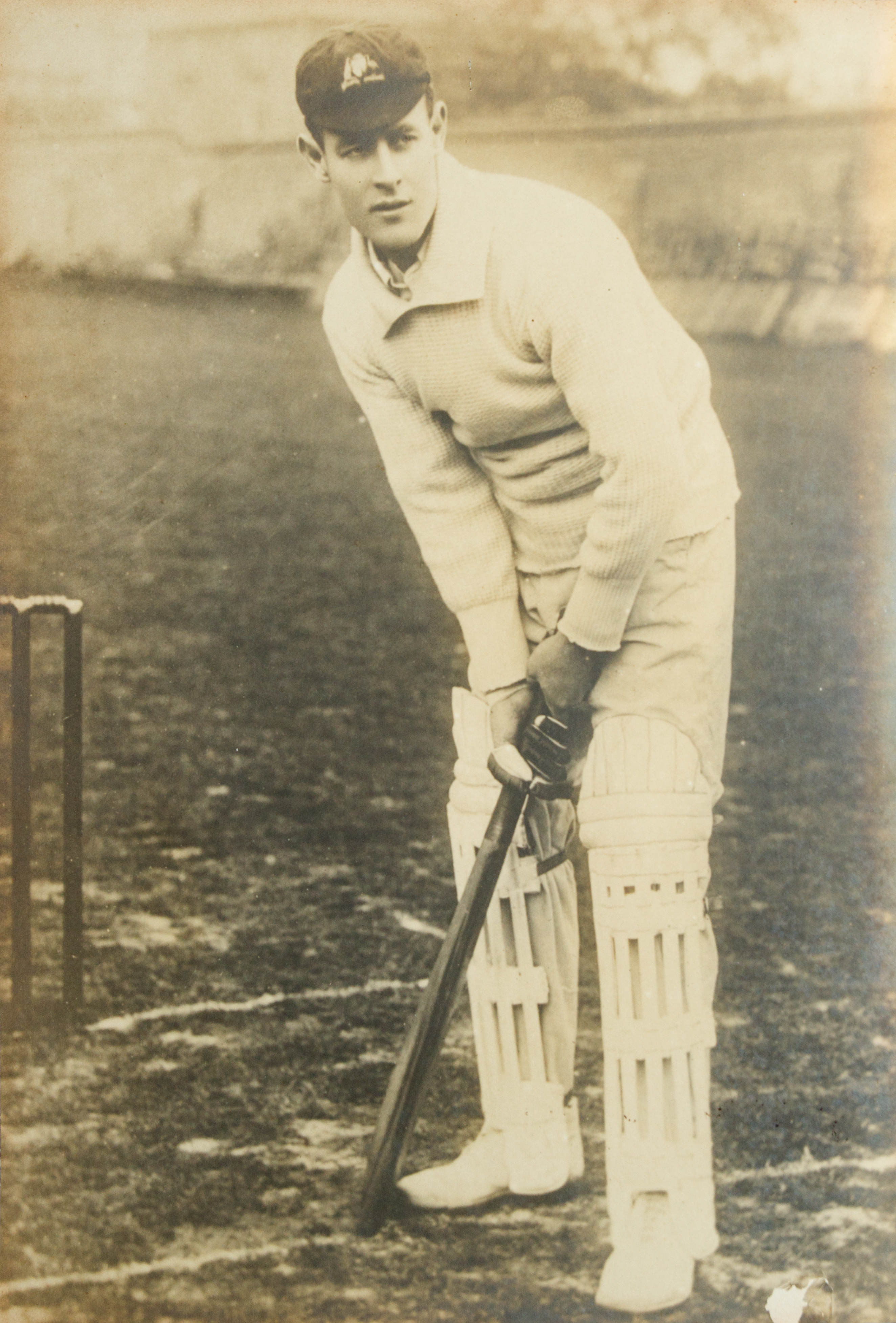

could have been my first reading of Arthur Mailey’s recollection of

bowling to him in club cricket, with its famous last line (“I felt

like a boy who had killed a dove”). It could have been my first

viewing, in the Lord’s museum, of that iconic photo by George

Beldam of Trumper jumping out to drive, taken at the Oval when

Australia played Surrey in July 1902. Whatever triggered it, my

obsession became total and all-absorbing. I read everything I could

about the man, spent a fortune on books and ephemera and bitterly

rued the impossibility of time travel, because unlike Harold Pinter

with Len Hutton, I never saw Trumper in his prime, and it was another

time - a time when a batsman could successfully break the shackles of

orthodoxy, could have stories told about his greatness as a human

being and as a cricketer. That fascinated me just as much as the man.

|

| Courtesy: arcadia.com |

His

accomplishments glow like an illuminated manuscript amongst fusty

tomes. 300 not out against Sussex at Hove on his first tour to the

“mother country” in 1899; first man to score a century before

lunch on the first day of a Test match, at Old Trafford in that damp

but glorious annus mirabilus of 1902; 335 in 180 minutes for

Paddington against Redfern in 1903; that last, poignant hurrah at

Lancaster Park where he contributed 293 to a record 8th wicket

partnership of 433 with Arthur Sims for a touring eleven against

Canterbury. That was in 1914; fifteen months later he was dead from

kidney disease. News of his passing knocked the Great War off the

front pages, and thousands of Sydneysiders lined the streets to watch

his funeral cortege on its way to Waverley Cemetery.

He

excelled on sticky wickets and his career encompassed innings of

adamantine resistance and furious blitzkrieg, with a distinct

preference for the latter; he broke windows while breaking bowlers’

spirits. True, there are others whose achievements impress more, by

sheer weight of numbers - Trumper’s Test average was 39.04 - but it

was in the manner of their making that he assured for himself

sporting immortality. “He has no style, and yet he is all style,”

CB Fry wrote. “He has no fixed canonical method of play, he defies

all the orthodox rules, yet every stroke he plays satisfies the

ultimate criterion of style - minimum of effort, maximum of effect.”

Mrs Fry seemed rather taken with him as well, rhapsodizing once in a

magazine of the time over his “splendid neck bared to the wind...

Trumper is an artist... a white-flannelled knight”. The reactions

of a mongoose, the looks of an Adonis, with feet that danced like

Fred Astaire’s; as Cardus has noted, he was the eagle to Don

Bradman’s jet plane, the free spirit that emptied the bars compared

to the relentless run-machine that would often prompt merely a

cursory glance up at the scoreboard to register that another hundred

had been added to the total.

His

achievements have gained mythical status through the lens of time and

distance, and stories of his kindness and generosity are legion -

cricket equipment given away to needy youngsters, newspaper boys sent

home in the rain with pockets full of money, team mate Reg Duff’s

funeral paid for out of his own pocket when a whip-round failed to

produce enough. The other side of the coin tells a rather different,

gloomier story; he was a failure in business, and died debt-ridden,

leaving his wife and children in poverty. His pecuniary incompetence

was notorious enough that the New South Wales Cricket Association

kept the money raised during his 1913 testimonial in trust, for fear

he would mismanage it.

My

plan to make a pilgrimage to Victor Trumper’s grave was hatched in

the winter of 2006. A nebulous daydream, over time it coalesced and

merged with a desire to watch England play the final two Tests of the

2010-11 Ashes series, at Melbourne and Sydney. I didn’t care that

the distinct possibility existed that the series would be over by

then: I wanted to see England play overseas, and I wanted to visit

the land of my hero, visit the places that were important to him,

walk in his footsteps.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

Hell

and high water didn’t come, but the big freeze did, in the form of

ferociously cold weather and snow-storms that brought the UK and

Heathrow Airport to a standstill. Flight QF030 to Melbourne was the

last plane to leave that day. Nothing does more to remedy a

nervousness about flying than desperation for your journey to begin.

That

journey ended at a hilltop cemetery overlooking the Tasman Sea, the

sun beating down, the waves booming against the sandstone cliffs.

Chris Tremlett had taken the final Australian wicket that won England

the series shortly before noon that day; by 3 o’clock I was

standing at Trumper’s grave.

As

resting places for great men go, it’s a pretty humble affair. The

large celtic cross that I used as a pointer to its location doesn’t

even belong to him; it merely backs onto his plot from someone

else’s. As I placed my flowers, there seemed no evidence of recent

visitation, and that surprised me. I’ve seen photos of John

Goddard’s West Indies team paying tribute at the grave back in

1950, and in 1977 Bob Simpson laid a wreath to commemorate the

centenary of Victor’s birth. I don’t think I was expecting

anything along the lines of the litter of tributes that adorns Jim

Morrison’s grave in Père Lachaise, but it felt like no-one had

been here for a long time. The leaded letters that spell out Victor’s

name are cracked and falling away; a tangible reminder that he is, as

Cardus wrote, “now part of the impersonal dust”.

But

it was a peculiarly moving moment for me, standing in this deserted

place of rest next to a neglected grave, still buzzing a little from

the excitement and emotion of watching England win, and the slightly

surreal feeling of actually being there. During my stay in Sydney I’d

also managed to visit some other locations central to the Trumper

legend: the sites of his old sports stores, the house he lived in in

Paddington - with its Audis, BMWs and Saabs a considerably more

gentrified area than it was in Victor’s day - and I’d retraced

his footsteps up through Surry Hills and through the park he played

cricket in as a boy each day as I walked to the SCG. The streets of

Sydney achieved an almost psychogeographical significance; by the

time the day of my departure came and the coach was taking me to the

airport I felt like I was seeing the city through Victor’s eyes.

This

June, Victor Trumper will have been dead for 97 years, but those who

came after him and named him as their inspiration carried on his

legacy of winged batsmanship, with a line of descent that included

Charlie Macartney, Archie Jackson, and Alan Kippax, and more recently

in spirit with Viv Richards and Virender Sehwag - torchbearers and

gamechangers all. I like to think that if Victor was alive now he’d

still be playing that raised-leg yorker shot to the square leg

boundary for four, still clashing heads with administrators over

players’ earnings, maybe even coining it in for an IPL franchise in

between scoring 56-ball hundreds for Australia; he knew his worth as

a player when he was alive, and I’m sure he would be as conscious

of his power to pull in the crowds now.

I’d

love to go back to Australia some day. I’m a Scottish-born England

fan whose favourite cricketer is an Australian; I’ve never had much

time for jingoism or loyalties that are defined only by borders. My

admiration for Victor Trumper took me to Australia; I fell in love

with the country and its people as well. England waited 24 years to

win a series in Australia; I had been planning my journey for four of

them. One day, I hope I can return, and follow in Victor’s

footsteps once more.

No comments:

Post a Comment